July 24, 2007. Swakopmund and Walvis Bay, Namibia.

Of all the stories that I've shot in my career, I've felt for a long time that this particular story was going to be a creative test -- and not just for me, but for the entire crew. The story itself is extremely compelling: explosions of hydrogen sulfide off the coast of Namibia have been killing ten's of thousands of fish. The mystery: how big are the explosions, what's causing them and what can be done -- if anything -- to lessen the impact?

The problem: There's very little that we can actually shoot. We don't have the time or money to wait for such an event to occur and most of the action, the sleuthing, takes place in minds of the scientists.

During the morning of our scout, we were guided by Kathy who lead us through the Ministry Building in a search for possible locations. The offices and the building were handsome and perched on the edge of the sea, but we'd traveled the whole way to Namibia, and shooting indoors just didn't seem right. Guided by our Production Assistant, Richard Berkley, we headed first to the desert and then on to Walvis Bay to continue our scout.

In the desert, Richard identified a number of locations, one of which might serve for a sequence when our scientists were considering the role of the desert in the story of explosive events. The desert was very impressive, and I began thinking that perhaps this location could play a bigger role in our story. As a location it was very cinematic but how could we use it . . . that was the question?

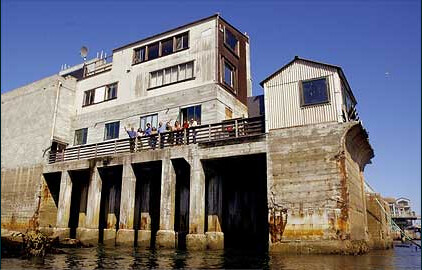

Next we headed off to Walvis Bay to scout possible warehouse locations at a place called Tuna Corp. In pictures that Richard sent to us, Tuna Corp's warehouses exuded a certain ambiance that might lend itself well to a series of sequences where our scientists were discussing potential scenarios that could explain the explosions in Namibia's waters. At Tuna Corp, we were met by George Pkuhn, who was going to guide us through the facility. Within a few short minutes of our tour, George mentioned that he was in the film business, too. I've heard this line a number of times, and I politely asked what he did. As George began speaking, I stopped dead.

"Did you say explosives?" I asked.

"Yes," George said. "I rig explosives for concerts and movies."

"What kind of explosives? Could you rig something pretty big with a lot of fire?"

"Sure, sure. That's what I do."

As we toured the warehouses at Tuna Corp, which proved to be very photogenic, I continued to question George about the possibility of rigging some explosives for us. I wasn't sure how I would use them, but if we could get explosives, I was sure that I could come up with something that would make sense.

As we left Tuna Corp, things were starting to come together. The ingredients:

1. A cool desert with amazing sand dunes

2. Railroad tracks that bisected part of the desert.

3. The potential of explosives.

4. Several empty warehouses with great lights and shadows.

How could these ingredients be used?

George Pkuhn is an explosive expert with decades of experience. The fact that George was missing one hand, and that we were going to try to put explosive into the film within a few short days, unnerved some of the crew just a little.

Chad, our assistant cameraman walks the desert . . .

. . . and his own sense of internal coolness . . .

. . . keeps him quite comfortable.